As you can see from the pile of triple store/RDBMS related posts below, I’ve recently moved out of my comfort zone to explore a new territory: Linked data, SPARQL, and OBDA (Ontology-Based Data Access). Last year, the FishDelish project, which was steered by researchers at the Manchester University, created a linked data version of FishBase, a large database containing information about most of the world’s fish species (around 30,000). Access to such a large amount of (nice and real) data offered a good opportunity for further usage, and so we set out to generate a cross-system performance benchmark using the FishBase data and queries. While the resulting paper (which I co-authored with Bijan Parsia, Sandra Alkiviadous, David Workman, Rafael Goncalves, Mark Van Harmelen, and Cristina Garilao) wasn’t nearly as comprehensive as I had wished, I did learn a lot on the way which didn’t make it into the paper. Nevertheless, here’s a few thoughts about performance benchmarking of data stores, including a wish list for my “ideal benchmarking framework”.

Performance benchmarking in Java: It’s complicated.

Measuring execution time of Java code in Java code is known to be tricky when you’re moving in sub-second territory. The JVM requires special attention, such as a warm-up phase and repeated measurements to take into account garbage collection. A lot has been written about this topic, so I shall refer you to this excellent post on “Robust Java Benchmarking” by Brent Boyer. On my wish list goes a warm-up phase which runs until the measurements are stabilised (rather than a fixed number of runs).

Getting the test data & queries

That’s an interesting one. There seem to be two kinds of SPARQL benchmarks: Those that use an existing dataset and fixed queries, taken from a real-world application, perhaps with some method of scaling the data (e.g. the DBpedia benchmark). And then there are benchmarks which artificially generate test data and queries based on some “realistic” application (e.g. LUBM, BSBM). Either way, we are tied to the data (of varying size) and queries. For our paper (and further, for Sandra’s dissertation), we tried to add another option to this mix: A framework that could turn any kind of existing dataset into a benchmark for multiple platforms.

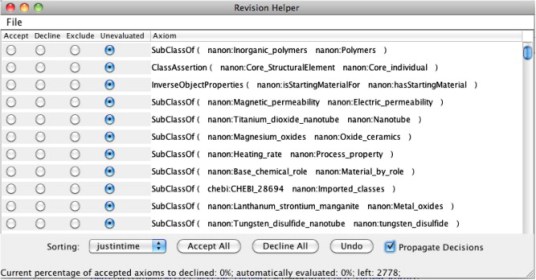

The framework (we called it MUM-benchmark, Manchester University Multi-platform benchmark) requires three things: A datastore (e.g. a relational DB) with the data, a set of queries, and a query mix. Each query is made up of a) a parameterised query (i.e. a query which contains one or more parameters) and b) a set of queries to query the database and obtain parameter values. In our implementation, the queries are held in a simple XML file – one for each query type (e.g. SPARQL, SQL). If there is an existing application for the data, the parameterised queries can simply be taken from the most frequently executed queries. In the case of FishBase, for example, we reverse-engineered queries to query for a fish species by common name, generate the species page, etc.

Additionally, I hacked BSBM to work with various datastores and added a standard SQL connection and an OBDA connection. While we have only tested our framework with the Quest OBDA system (with a FishBase ontology written by Sandra), this should work for all other OBDA systems, too (and if not, it’s fairly straightforward to add another type of connection).

One aspect which we haven’t had the time to implement is scaling the FishBase data by species. Ideally, we want a simple mechanism to specify the number of species we want in our data and get a smaller dataset. If we take this one step further, we could also artificially generate species based on heuristics from the existing data in order to increase the total number of species beyond the existing ones.

To my wish list, I add cross-platform benchmarks, generating a benchmark from existing data, scalable datasets, and easy extension by additional queries.

What to measure?

Query mixes seem to be the thing to go for when benchmarking RDF stores. A query mix is simply an ordered list of (say, 20-25) query executions which emulates “typical” user behaviour for an application (e.g. in the “explore use case” of BSBM: find products for given features, retrieve information about a product, get a review, etc.) This query mix can either be an independent list of queries (e.g. the parameter values for each query are independent of each other) or a sequence, in which the parameter value of a query depends on previous queries. As the latter is obviously a lot more realistic, I shall add it to my wish list.

For the FishDelish benchmark, we were kindly given the server logs for one month’s activity on one of the FishBase servers, from which we generated a query mix. It turned out that on average, only 5 of the 24 queries we had assembled were actually used frequently on FishBase, while the others were hardly seen at all (as in, 4 times out of 30,000 per month). Since it was not possible to include these into the query mix without deviating significantly from reality, we generated another “query mix” which would simply measure each query once. As the MUM-benchmarking framework wouldn’t do sequencing at the time, there was no difference between a realistic query mix and a “measure all queries once” type mix.

Finally, the third approach would be a “randomised weighted” mix based on the frequency of each query in the server logs. The query mix contains the 5 most frequent queries, each instantiated n times, where is the (hourly, daily) frequency of the query according to the server access logs.

How to measure!?

Now we’re back to the “robust Java benchmarking” issue. It is clear that we need a warm-up phase until the measurements are stabilised, and repeated runs to obtain a reliable measurement (e.g. to take into account garbage collection which might be triggered at any point and add a significant overhead to the execution time).

In the case of the MUM-benchmark, we generate a query set (i.e. “fill in” parameter values for the parameterised queries), run the query mix 50 times as a warm-up, then run the query mix several hundred times and measure the execution time. This is repeated multiple times with distinct query sets (in order to avoid bias caused by “good” or “bad” query parameter values). As you can see, this method is based on “run the mix x times” rather than “complete as many runs as you can in x minutes (or hours)”. This worked out okay for our FishBase queries, as the run times were reasonably short, but for any measurements with significantly longer (or simply unpredictable) execution times, this is completely impractical. I therefore add “give the option to measure runs per time” (rather than fixed number) to my wish list.

The results

This was something I found rather pleasant about the BSBM framework. The benchmark conveniently generates an XML results file for each run, with summary metrics of the entire query mix, and metrics for each individual query. As our query mix was run with different parameters, I added the complete query string to the XML output (in order to trace errors, which came in quite handy for one SPARQL query where the parameter value was incorrectly generated). The current hacky solution generates an XML file for each query set, which are then aggregated using another bit of code – eventually the output format should be a little more elegant than dozens of XML files (and maybe spit out a few graphs while we’re at it).

Conclusions

While modifying the BSBM framework I put together the above “wish list” for benchmarking frameworks, as there were quite a few things that made performing the benchmark unnecessarily difficult. So for the next version of the MUM-benchmarking framework, I will take these issues into account. Overall, however, the whole project was extremely interesting – setting up the triple stores, generating the queries, tailoring (read: hacking) BSBM to work across multiple platforms (a MySQL DB, a Virtuoso RDF store, a Quest OBDA system over a MySQL db) and figuring out the query mixes.

Oh. And I learned a lot about fish. The image shows a zebrafish, which was our preferred test fish for the project.

[cc-licensed image by Marrabio2]

You must be logged in to post a comment.